The fall of the Afghan Republic on August 15, 2021 was not the result of a single cause; it was the outcome of several simultaneous forces: the external shift triggered by the Doha Agreement and the withdrawal of vital support, long-standing structural weaknesses in state-building after the U.S. intervention (centralization, corruption, legitimacy deficits, and elite fragmentation), and the Taliban’s operational and psychological strategy built on gradual encirclement and local surrender deals. Through an interdisciplinary lens, this analysis examines these drivers at the international, state, and battlefield levels, showing that the “moment of collapse” was less the beginning of defeat and more the convergence point of accumulated failures.

The central question is: what drivers pushed actors’ decisions in ways that led to the Afghan Republic collapsing within weeks?

The answer lies across three layers:

first, the international environment, which reshaped expectations and calculations; second, the Afghan state and Kabul’s political–security institutions, which showed weak resilience to external shock; and third, the military-operational level, where the Taliban fused battlefield pressure, political negotiation, and information warfare to enable a “collapse without major urban fighting.”

International Level: Shifting Expectations and the Erosion of Pillars

The February 2020 Doha Agreement was a decisive inflection point in the engineering of expectations. Excluding the Afghan government from the core negotiations and establishing a fixed withdrawal timeline created a widespread perception—among the public and elites—that the Taliban were the “government in waiting” and the Republic a “project nearing its end.”

In theories of war and politics, shifts in expectations matter as much as shifts in material balance: once local actors view the future as predetermined, willingness to resist declines and incentives to bargain rise.

At the same time, the withdrawal of international forces was not only the departure of personnel; it included the loss of the contractor, maintenance, intelligence, and air-support networks that formed the backbone of Afghan security forces’ effectiveness. An army structurally dependent on external mobility, targeting, medical evacuation, and repair capabilities quickly lost cohesion and morale. Added to this was the release of thousands of Taliban prisoners—an infusion of manpower and psychological momentum.

State and Institutional Level: Long-Term Weaknesses and Short-Term Miscalculations

State-building after 2001 advanced through extreme centralization, entrenched corruption, a rent-based political economy, and highly contested elections. This architecture did not produce a “stable state coalition,” but rather a fragile web of short-term, personalized loyalties.

One direct consequence was a limited capacity to mobilize society against the Taliban: in many areas where the state failed to offer services or justice, it lacked the social capital required for a prolonged fight.

At the leadership level, instability in security appointments, long-standing elite rivalries (from the National Unity Government era to the 2019 election crisis), and dependence on narrow decision-making circles weakened Kabul’s negotiating leverage and battlefield initiative.

A recurring miscalculation also played a role: genuine disbelief in a rapid, full U.S. withdrawal, which delayed painful institutional reforms and political mobilization.

On the security side, Afghanistan’s forces were optimized for high-mobility operations backed by close air support, not for independent, long-duration defense. When the “active defense” doctrine replaced offensive initiative, the crucial element of “seizing the initiative”—vital in insurgency warfare—was lost, and units were pushed into point-holding rather than breaking sieges.

Operational Level: The Strategy of “Gradual Encirclement” and Surrender-Driven Collapse

From mid-2020 onward, the Taliban recalibrated their offensive model: first seizing rural arteries and border routes to choke supply lines, then encircling district centers, and finally concentrating on provincial capitals.

But the key was not merely military superiority—it was the network of local agreements with powerbrokers, commanders, and intermediaries, offered with promises of immunity, shared positions, or acceptance of the inevitable. These deals made resistance “irrational and costly.”

Information and psychological warfare were integral: targeted military displays, publicized surrender lists, and the narrative of an “inevitable end” spread through media and local networks, steadily eroding defenders’ morale. Once a few provincial capitals fell with minimal fighting, contagion effects accelerated, culminating in Kabul’s collapse without major urban combat.

Regional Dimension: Strategic Depth, Informal Economies, and Neighboring Actors

Afghanistan’s geopolitical setting ensured the conflict was never purely internal. External sanctuaries, support networks, and cross-border informal economies (fuel, narcotics, trade routes) allowed the Taliban to sustain manpower and financing beyond what an isolated insurgency could manage.

Regionally, periodic yet persistent interactions between the Taliban and elements in Pakistan, alongside the strategic calculations of Iran, China, Russia, and Gulf states, narrowed Kabul’s room for maneuver. Despite divergent narratives on the exact extent of “external support,” most analyses converge on one point: without cross-border depth, the cost of resisting the Taliban for local communities and elites would have been far lower, and surrender dynamics would not have unfolded so rapidly.

Discussion: “Necessary Cause,” “Sufficient Cause,” and the Fallacy of Single-Factor Explanations

Methodologically, the withdrawal of vital external support was a necessary accelerant of collapse—but not alone sufficient. If the Afghan state had enjoyed deeper social legitimacy, broader coalition networks, and a less dependency-prone security design, it could—though at great cost—have slowed the collapse or reached a different political settlement.

Conversely, internal structural weaknesses alone would not necessarily have produced such sudden disintegration without the external shock. The conditions became sufficient only when the Taliban’s encirclement strategy aligned with diminishing international backing and deepening internal erosion.

Conclusion

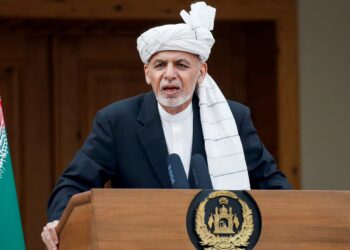

The fall of Ashraf Ghani’s government should be viewed as the convergent outcome of three forces: a transformed international environment and weakening of external support; institutional fragility and elite fragmentation within the Afghan state; and the Taliban’s operational–psychological initiative on the ground.

In this framework, August 15, 2021 was not an abrupt incident but the maturation of long-accumulating deficiencies. Looking forward, any future model of stabilization in Afghanistan will remain vulnerable to similar shocks unless political legitimacy is rebuilt, dysfunctional centralization reduced, institutional and security self-reliance strengthened, and the regional environment realistically managed.